Back to Menu

Letter from Jennifer

In 1973, when I was thirteen, flat chested, with braces…

and hadn’t gotten my period yet I spent the summer and fall at the farm of my riding teacher, Mrs. G. In between an intense regimen of equestrian training, Mrs. G introduced me to her running coach – an acclaimed athlete, named Bill – and I started training with him as well. To my complete delight, I became their favorite student and they often took me with them on private jaunts. Soon, Mrs. G suggested that I spend nights at Bill’s when I came to visit her so that Bill could get to know me better. That is how at age thirteen, I became Bill’s ‘lover’.

By the time I was fourteen, I decided I had to break up the relationship with them. I never saw Mrs. G or Bill again for forty years. It was as if I froze them in time in that moment and they were suspended forever in a black hole. But the story stayed with me as I grew up as this huge question mark: Why me? Why them? Who were they? Who was I?

From the beginning, I sought to put the event into some artistic form: from the first time, I scribbled a thinly veiled fictional short story that I handed in to my eighth grade English class, which I called “The Tale”; to at midlife, as a veteran filmmaker, writing a script based on my adolescent writings versus my adult memories – in all their contradicting complexity.

The result is THE TALE, a film memoir of how a thirteen-year-old girl chose to forge her own version of events in order to create the identity she wanted to have and the woman she would become.

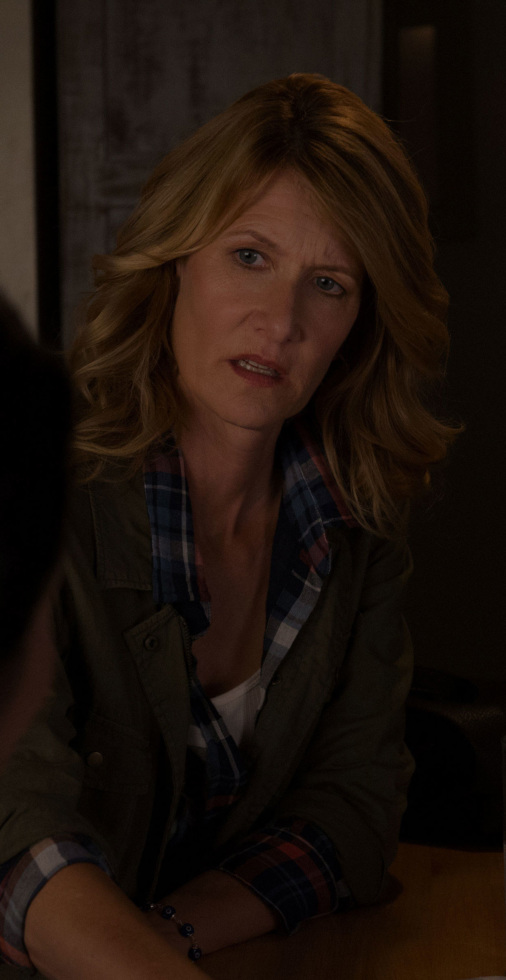

Filmmaker Jennifer Fox of THE TALE, Jennifer Fox takes a riding lesson at 13.

“To really take care of the soul we have to allow all the truth in all its complexity and honor the contradictions.”

From the beginning, it was important to me that this film represented an authentic tapestry of my experience. I wanted to give all the parts of the story a voice and particularly my thirteen-year-old self. As we grow up, we so often erase the feelings we had as children, as if they were negligible, but I think that is disingenuous. I wanted to explore that 13-year old me and honor her feelings. But when I returned to her story as an adult, I didn’t know who she was any more. I realized that I was a different person back then, and that if she had met my woman-self she would hate me, as another one of those ‘stupid adults’ who didn’t understand her. But if I met my thirteen-year-old self now, I would have thrown my body in front of her and done anything to stop the decisions she was about to make.

Our perspective and the stories we tell ourselves change all the time and we are taught that one story erases the next in an ever-turning funnel toward this thing called ‘the truth’. That is western ideology, I dare say the essence of Freudian concepts. But as I grow older, I realize that the truth has many parallel stories that live like a layer-cake simultaneously in our lives. To really take care of the soul we have to allow all the truth in in all its complexity and honor the contradictions.

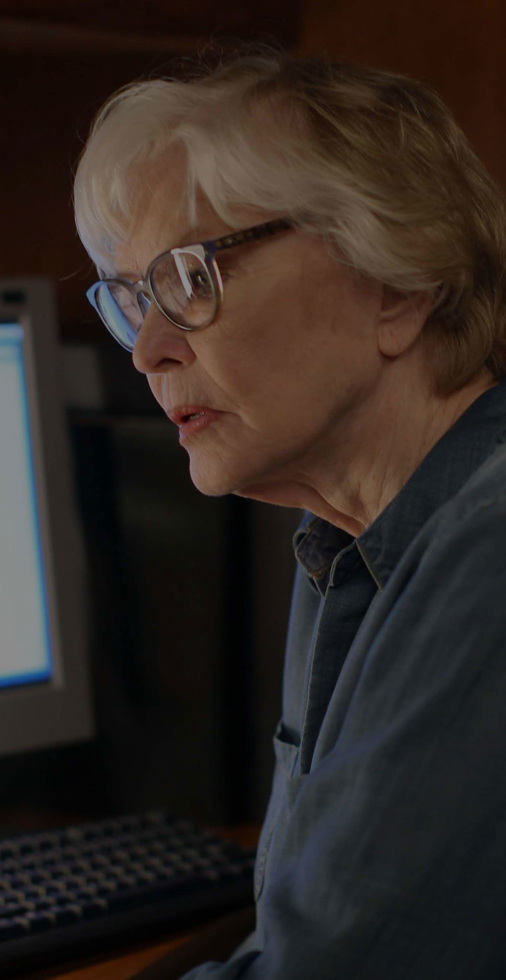

Filmmaker Jennifer Fox with actress Isabel Nelisse (Jenny) on the set of the THE TALE, watching playback of a scene on a handheld monitor.

This is what I tried to do in THE TALE. At the end, I hope that Jenny’s feelings and my adult realizations can live side by side. This is no way to sidestep the horror of child sexual abuse that has existed since time immemorial. We have to use all our power to prevent what happened to me from happening to other children. Simultaneously, in order to help survivors heal we have to acknowledge the range and nuances of feelings that occur in this complex process that ensnares children.

Child sexual abuse is one of the most taboo subjects on the planet and It is mystified and left hazy so as not to face the horror. That is why I felt it was important that I not shy away from showing the physical scenes you see in the film. The scenes and dialogue in THE TALE come from my very detailed memory of those events. They are included to show how painful and confusing this event was for me – and the true awfulness of it.

“Child sexual abuse is one of the most taboo subjects on the planet and it is mystified and left hazy so as not to face the horror.”

Moreover, I decided to leave the main character Jennifer’s name my own in THE TALE while fictionalizing the other’s names, because I wanted the viewer to have to wrestle with the reality of the events. I felt strongly that if I took a distance from the truth of the story as most writers do by fictionalizing their names, there would be no one to stand up by the film and answer the nay-sayers and deniers who want to tell us, it can’t be like this. By leaving the Jennifer character’s name as mine, I am there to tell them, “no, this really happened. And yes, I did really feel ‘love’ for these people as they robbed me of my trust and betrayed and hurt me.”

Bottom line, if we don’t talk about how complicated this is for the child, and how adept the perpetrator is at ensnaring their heart in a web of complicity, we can never prevent it from happening or help survivors heal. We have to look this in the eye to change the conversation around trauma, protective memory, and abuse.

Jennifer Fox

Filmmaker, THE TALE